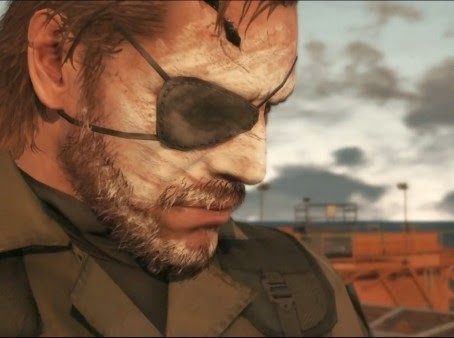

“Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain” does this beautifully by letting Kochai’s protagonist rewrite history and save his father’s brother from being killed by Russian soldiers, which is what happened in the protagonist’s real (fictional) life. My status as the hero facing the enemy, as the subject facing the object, falls apart.” “There I am in the game, playing as a white soldier, and all of a sudden I’m murdering an Afghan man who looks just like my father. “For me this sense of becoming the shooter in first-person gameplay was often disrupted by the depiction of the enemies in video games like Call of Duty,” he said. Kochai talked a little about it in an interview with Deborah Treisman, The New Yorker’s fiction editor, and cites that disjunction between video game subject and object as the reason he chose to write the whole thing in the second person.

“The fact that nineteen-eighties Afghanistan is the final setting of the most legendary and artistically significant gaming franchise in the history of time made you all the more excited to get your hands on it, especially since you’ve been shooting at Afghans in your games ( Call of Duty and Battlefield and Splinter Cell) for so long that you’ve become oddly immune to the self-loathing you felt when you were first massacring wave after wave of militant fighters who looked just like your father,” Kochai writes. As you learn later, the protagonist is Afghan. The effect is video game-y, alienating in just the right way.

(Obviously there is much more to the story it is a beautifully textured piece of writing.) One of the more remarkable things about Kochai’s story is its use of the second person. In Kochai’s story, the unnamed protagonist - “you” - begins playing the game while avoiding his father, and eventually realizes that his father and his father’s dead brother are in it. The Phantom Pain came out in 2015, and its events unfold against the backdrop of the Soviet-Afghan War, which began in 1979 and ended a decade later. But it’s so much more than that, which is obvious from the first paragraph.įirst, you have to gather the cash to preorder the game at the local GameStop, where your cousin works, and, even though he hooks it up with the employee discount, the game is still a bit out of your price range because you’ve been using your Taco Bell paychecks to help your pops, who’s been out of work since you were ten, and who makes you feel unbearably guilty about spending money on useless hobbies while kids in Kabul are destroying their bodies to build compounds for white businessmen and warlords-but, shit, it’s Kojima, it’s Metal Gear, so, after scrimping and saving (like literal dimes you’re picking up off the street), you’ve got the cash, which you give to your cousin, who purchases the game on your behalf, and then, on the day it’s released, you just have to find a way to get to the store. It does what it says on the tin: the story is about a teenager playing Hideo Kojima’s Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. Which is the feeling I got when I read Jamil Jan Kochai’s phenomenal short story “Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain” in this week’s issue of The New Yorker. “They wish they could live as purposefully as fictional characters constructed around all-consuming psychological motivations, but not enough to change their lives.”) The best fiction - the best narratives - on the other hand, get close enough to the real thing that they feel alive, a living and breathing thing. (As Nell Zink wryly observes in her latest piece about translation: real people don’t work backward. Narratives lie because they make sense out of the nonsense of everyday life they’re always retroactive. It’s not meant to be, really, because the form is a reflection.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)